Introduction

In September 2023, Darktrace published its first Half-Year Threat Report, highlighting Threat Research, Security Operation Center (SOC), model breach, and Cyber AI Analyst analysis and trends across the Darktrace customer fleet. According to Darktrace’s Threat Report, the most observed threat type to affect Darktrace customers during the first half of 2023 was Malware-as-a-Service (Maas). The report highlighted a growing trend where malware strains, specifically in the MaaS ecosystem, “use cross-functional components from other strains as part of their evolution and customization” [1].

Darktrace’s Threat Research team assessed this ‘Frankenstein’ approach would very likely increase, as shown by the fact that indicators of compromise (IoCs) are becoming “less and less mutually exclusive between malware strains as compromised infrastructure is used by multiple threat actors through access brokers or the “as-a-Service” market” [1].

Darktrace investigated one such threat during the last months of summer 2023, eventually leading to the discovery of CyberCartel-related activity across a significant number of Darktrace customers, especially in Latin America.

CyberCartel Overview and Darktrace Coverage

During a threat hunt, Darktrace’s Threat Research team discovered the download of a binary with a unique Uniform Resource Identifier (URI) pattern. When examining Darktrace’s customer base, it was discovered that binaries with this same URI pattern had been downloaded by a significant number of customer accounts, especially by customers based in Latin America. Although not identical, the targets and tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) resembled those mentioned in an article regarding a botnet called Fenix [2], particularly active in Latin America.

During the Threat Research team’s investigation, nearly 40 potentially affected customer accounts were identified. Darktrace’s global Threat Research team investigates pervasive threats across Darktrace’s customer base daily. This cross-fleet research is based on Darktrace’s anomaly-based detection capability, Darktrace DETECT™, and revolves around technical analysis and contextualization of detection information.

Amid the investigation, further open-source intelligence (OSINT) research revealed that most indicators observed during Darktrace’s investigations were associated to a Latin American threat group named CyberCartel, with a small number of IoCs being associated with the Fenix botnet. While CyberCartel seems to have been active since 2012 and relies on MaaS offerings from well-known malware families, Fenix botnet was allegedly created at the end of last year and “specifically targets users accessing government services, particularly tax-paying individuals in Mexico and Chile” [2].

Both groups share similar targets and TTPs, as well as objectives: installing malware with information-stealing capabilities. In the case of Fenix infections, the compromised device will be added to a botnet and execute tasks given by the attacker(s); while in the case of CyberCartel, it can lead to various types of second-stage info-stealing and Man-in-the-Browser capabilities, including retrieving system information from the compromised device, capturing screenshots of the active browsing tab, and redirecting the user to fraudulent websites such as fake banking sites. According to a report by Metabase Q [2], both groups possibly share command and control (C2) infrastructure, making accurate attribution and assessment of the confidence level for which group was affecting the customer base extremely difficult. Indeed, one of the C2 IPs (104.156.149[.]33) observed on nearly 20 customer accounts during the investigation had OSINT evidence linking it to both CyberCartel and Fenix, as well as another group known to target Mexico called Manipulated Caiman [3] [4] [5].

CyberCartel and Fenix both appear to target banking and governmental services’ users based in Latin America, especially individuals from Mexico and Chile. Target institutions purportedly include tax administration services and several banks operating in the region. Malvertising and phishing campaigns direct users to pages imitating the target institutions’ webpages and prompt the download of a compressed file advertised in a pop-up window. This file claims enhance the user’s security and privacy while navigating the webpage but instead redirects the user to a compromised website hosting a zip file, which itself contains a URL file containing instructions for retrieval of the first stage payload from a remote server.

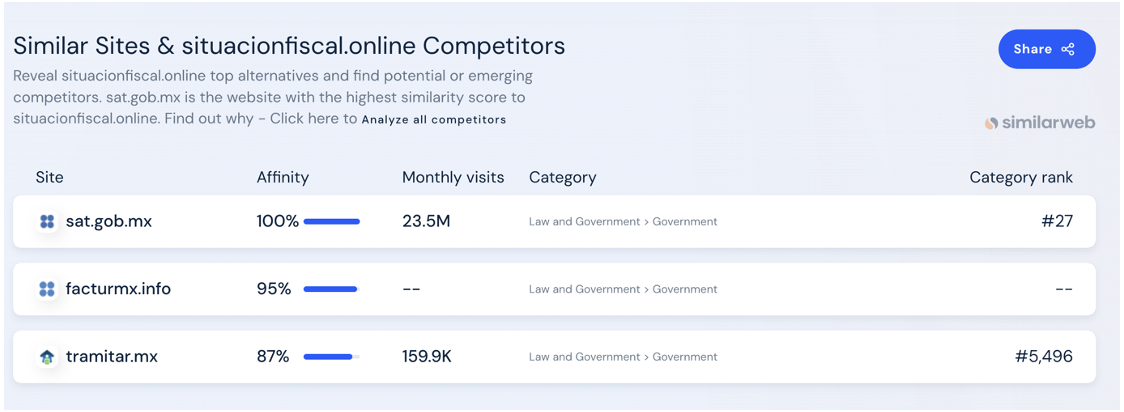

During their investigations, the Threat Research team observed connections to 100% rare domains (e.g., situacionfiscal[.]online, consultar-rfc[.]online, facturmx[.]info), many of them containing strings such as “mx”, “rcf” and “factur” in their domain names, prior to the downloads of files with the unique URI pattern identified during the aforementioned threat hunting session.

The reference to “rfc” is likely a reference to the Registro Federal de Contribuyentes, a unique registration number issued by Mexico’s tax collection agency, Servicio de Administración Tributaria (SAT). These domains were observed as being 100% rare for the environment and were connected to a few minutes prior to connections to CyberCartel endpoints. Most of the endpoints were newly registered, with creation dates starting from only a few months earlier in the first half of 2023. Interestingly, some of these domains were very similar to legitimate government websites, likely a tactic employed by threat actors to convince users to trust the domains and to bypass security measures.

In other customer networks, connections to mail clients were observed, as well as connections to win-rar[.]com, suggesting an interaction with a compressed file. Connections to legitimate government websites were also detected around the same time in some accounts. Shortly after, the infected devices were detected connecting to 100% rare IP addresses over the HTTP protocol using WebDAV user agents such as Microsoft-WebDAV-MiniRedir/10.0.X and DavCInt. Web Distributed Authoring and Versioning, in its full form, is a legitimate extension to the HTTP protocol that allows users to remotely share, copy, move and edit files hosted on a web server. Both CyberCartel and Fenix botnet reportedly abuse this protocol to retrieve the initial payload via a shortcut link. The use (or abuse) of this protocol allows attackers to evade blocklists and streamline payload distribution. In cases investigated by Darktrace, the use of this protocol was not always considered unusual for the breach device, indicating it also was commonly used for its legitimate purposes.

HTTP methods observed included PROPFIND, GET, and OPTIONS, where a higher proportion of PROPFIND requests were observed. PROPFIND is an HTTP method related to the use of WebDAV that retrieves properties in an exactly defined, machine-readable, XML document (GET responses do not have a define format). Properties are pieces of data that describe the state of a resource, i.e., data about data [7]. They are used in distributed authoring environments to provide for efficient discovery and management of resources.

In a number of cases, connections to compromised endpoints were followed by the download of one or more executable files with names following the regex pattern /(yes|4496|[A-Za-z]{8})/(((4496|4545)[A-Za-z]{24})|Herramienta_de_Seguridad_SII).(exe|jse), for example 4496UCJlcqwxvkpXKguWNqNWDivM.exe. PROPFIND and GET HTTP requests for dynamic-link library (DLL) files such as urlmon.dll and netutils.dll were also detected. These are legitimate Windows files that are essential to handle network and internet-related tasks in Windows. Irrespective of whether they had malicious or legitimate signatures, Darktrace DETECT was able to recognize that the download of these files was suspicious with rare external endpoints not previously observed on the respective customer networks.

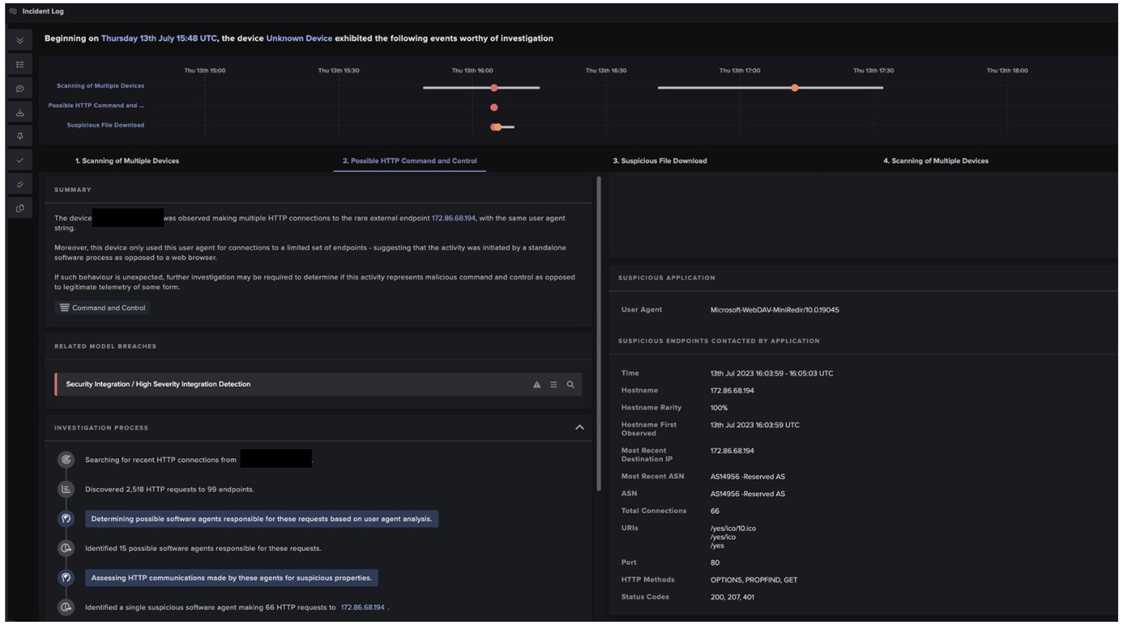

Following Darktrace DETECT’s model breaches, these HTTP connections were investigated by Cyber AI Analyst™. AI Analyst provided a summary and further technical details of these connections, as shown in figure 6.

AI Analyst searched for all HTTP connections made by the breach device and found more than 2,500 requests to more than a hundred endpoints for one given device. It then looked for the user agents responsible for these connections and found 15 possible software agents responsible for the HTTP requests, and from these identified a single suspicious software agent, Microsoft-WebDAV-Min-Redir. As mentioned previously, this is a legitimate software, but its use by the breach device was considered unusual by Darktrace’s machine learning technology. By performing analysis on thousands of connections to hundreds of endpoints at machine speed, AI Analyst is able to perform the heavy lifting on behalf of human security teams and then collate its findings in a single summary pane, giving end-users the information needed to assess a given activity and quickly start remediation as needed. This allows security teams and administrators to save precious time and provides unparalleled visibility over any potentially malicious activity on their network.

Following the successful identification of CyberCartel activity by DETECT, Darktrace RESPOND™ is then able to contain suspicious behavior, such as by restricting outgoing traffic or enforcing normal patterns of life on affected devices. This would allow customer security teams extra time to analyze potentially malicious behavior, while leaving the rest of the network free to perform business critical operations. Unfortunately, in the cases of CyberCartel compromises detected by Darktrace, RESPOND was not enabled in autonomous response mode meaning preventative actions had to be applied manually by the customer’s security team after the fact.

Conclusion

Threat actors targeting high-value entities such as government offices and banks is unfortunately all too commonplace. In the case of Cyber Cartel, governmental organizations and entities, as well as multiple newspapers in the Latin America, have cautioned users against these malicious campaigns, which have occurred over the past few years [8] [9]. However, attackers continuously update their toolsets and infrastructure, quickly rendering these warnings and known-bad security precautions obsolete. In the case of CyberCartel, the abuse of the legitimate WebDAV protocol to retrieve the initial payload is just one example of this. This method of distribution has also been leveraged by in Bumblebee malware loader’s latest campaign [10]. The abuse of the legitimate WebDAV protocol to retrieve the initial CyberCartel payload outlined in this case is one example among many of threat actors adopting new distribution methods used by others to further their ends.

As threat actors continue to search for new ways of remaining undetected, notably by incorporating legitimate processes into their attack flow and utilizing non-exclusive compromised infrastructure, it is more important than ever to have an understanding of normal network operation in order to detect anomalies that are indicative of an ongoing compromise. Darktrace’s suite of products, including DETECT+RESPOND, is well placed to do just that, with machine-speed analysis, detection, and response helping security teams and administrators keep their digital environments safe from malicious actors.

Credit to: Nahisha Nobregas, SOC Analyst

References

[1] https://darktrace.com/blog/darktrace-half-year-threat-report

[2] https://www.metabaseq.com/fenix-botnet/

[4] https://www.virustotal.com/gui/ip-address/104.156.149.33/community

[5] https://silent4business.com/tendencias/1

[6] https://www.metabaseq.com/cybercartel/

[7] http://www.webdav.org/specs/rfc2518.html#rfc.section.4.1

[8] https://www.csirt.gob.cl/alertas/8ffr23-01415-01/

[9] https://www.gob.mx/sat/acciones-y-programas/sitios-web-falsos

Appendices

Darktrace DETECT Model Detections

AI Analyst Incidents:

• Possible HTTP Command and Control

• Suspicious File Download

Model Detections:

• Anomalous Connection / New User Agent to IP Without Hostname

• Device / New User Agent and New IP

• Anomalous File / EXE from Rare External Location

• Multiple EXE from Rare External Locations

• Anomalous File / Script from Rare External Location

List of IoCs

IoC - Type - Description + Confidence

f84bb51de50f19ec803b484311053294fbb3b523 - SHA1 hash - Likely CyberCartel Payload IoCs

4eb564b84aac7a5a898af59ee27b1cb00c99a53d - SHA1 hash - Likely CyberCartel payload

8806639a781d0f63549711d3af0f937ffc87585c - SHA1 hash - Likely CyberCartel payload

9d58441d9d31b5c4011b99482afa210b030ecac4 - SHA1 hash - Possible CyberCartel payload

37da048533548c0ad87881e120b8cf2a77528413 - SHA1 hash - Likely CyberCartel payload

2415fcefaf86a83f1174fa50444be7ea830bb4d1 - SHA1 hash - Likely CyberCartel payload

15a94c7e9b356d0ff3bcee0f0ad885b6cf9c1bb7 - SHA1 hash - Likely CyberCartel payload

cdc5da48fca92329927d9dccf3ed513dd28956af - SHA1 hash - Possible CyberCartel payload

693b869bc9ba78d4f8d415eb7016c566ead839f3 - SHA1 hash - Likely CyberCartel payload

04ce764723eaa75e4ee36b3d5cba77a105383dc5 - SHA1 hash - Possible CyberCartel payload

435834167fd5092905ee084038eee54797f4d23e - SHA1 hash - Possible CyberCartel payload

3341b4f46c2f45b87f95168893a7485e35f825fe - SHA1 hash - Likely CyberCartel payload

f6375a1f954f317e16f24c94507d4b04200c63b9 - SHA1 hash - Likely CyberCartel payload

252efff7f54bd19a5c96bbce0bfaeeecadb3752f - SHA1 hash - Likely CyberCartel payload

8080c94e5add2f6ed20e9866a00f67996f0a61ae - SHA1 hash - Likely CyberCartel payload

c5117cedc275c9d403a533617117be7200a2ed77 - SHA1 hash - Possible CyberCartel payload

19dd866abdaf8bc3c518d1c1166fbf279787fc03 - SHA1 hash - Likely CyberCartel payload

548287c0350d6e3d0e5144e20d0f0ce28661f514 - SHA1 hash - Likely CyberCartel payload

f0478e88c8eefc3fd0a8e01eaeb2704a580f88e6 - SHA1 hash - Possible CyberCartel payload

a9809acef61ca173331e41b28d6abddb64c5f192 - SHA1 hash - Likely CyberCartel payload

be96ec94f8f143127962d7bf4131c228474cd6ac - SHA1 hash -Likely CyberCartel payload

44ef336395c41bf0cecae8b43be59170bed6759d - SHA1 hash - Possible CyberCartel payload

facturmx[.]info - Hostname - Likely CyberCartel infection source

consultar-rfc[.]online - Hostname - Possible CyberCartel infection source

srlxlpdfmxntetflx[.]com - Hostname - Likely CyberCartel infection source

facturmx[.]online - Hostname - Possible CyberCartel infection source

rfcconhomoclave[.]mx - Hostname - Possible CyberCartel infection source

situacionfiscal[.]online - Hostname - Likely CyberCartel infection source

descargafactura[.]club - Hostname - Likely CyberCartel infection source

104.156.149[.]33 - IP - Likely CyberCartel C2 endpoint

172.86.68[.]194 - IP - Likely CyberCartel C2 endpoint

139.162.73[.]58 - IP - Likely CyberCartel C2 endpoint

172.105.24[.]190 - IP - Possible CyberCartel C2 endpoint

MITRE ATT&CK Mapping

Tactic - Technique

Command and Control - Ingress Tool Transfer (T1105)

Command and Control - Web Protocols (T1071.001)